(111) S7E8 Nonviolent Action: Civil Rights

Welcome back to the Fourth Wave podcast. Today, we are continuing our series on nonviolent action. We will specifically be looking at nonviolent action in relation to the civil rights movement. While I'm sure, especially for US listeners, a lot of this discussion will be familiar to you, my hope is that I'll I'll draw out some observations and information which might help you to not only understand the movement historically, but that it will shed some light on both nonviolent strategy and race issues which are relevant today. So rather than look at the history proper of the civil rights movement, we'll be kind of pulling out some things and coming from some different angles.

Derek:Let's jump right in. So I was recently talking with someone about Black Lives Matter, and they made an interesting comment. At least it was it was interesting to me. They said, I understand where BLM is coming from, but why can't it be more like the civil rights movement? You just can't keep protesting for years and years because it it causes chaos and disruption.

Derek:It was almost like he was just saying, alright, alright, your voice has been heard, just get over it already. It was like, we hear you even though we're not doing anything about it, like, we heard you, you can shut up now, right? And and that's not how my friend meant it, like, he's a he was a good hearted person, but, you know, that's that's kinda what it sounded like to me. And due to his his ignorance on the topic, I I think he exposed a few important points that I want to hit on before getting into the civil rights discussion proper. First, the civil rights movement lasted anywhere from fifteen to twenty five years.

Derek:You know, if you count the beginning as Truman's order to desegregate the military in 1948, you know, if that's the start, and if it ends in the mid seventies when when riots kind of died down a bit, and protests and all that stuff, you get twenty five years. If you count from Brown versus the Board of Education in 1954 to the civil rights legislation in 1968, you get right around fifteen years. And I think the the fifty five to sixty eight date is probably better, at least starting in in '54, '50 '5, maybe ending in the early seventies. But the fifty five to sixty eight date corresponds with MLK's work as well, and it might be the easiest to pin down as the start and end of the specific movement being the civil rights movement because MLK is is kind of you know, the best known for for heading that up. But regardless of how you see the movement, it didn't just consist of a few protests here and there over the course of a year or two years or five years even.

Derek:But that's how I and a lot of others seem to think of it, or how I used to think of it. And I think that's kind of natural. The further you move away from a historical event, the more compressed you tend to make segments of history. And in this case, I think we're also ignorant of it. Not only do we compress it, but we're ignorant of how long such a struggle lasted.

Derek:You know, whereas the the last five years since Ferguson felt like a lifetime to my friend, the civil rights movement, though lasting three times as long at least, seemed like a shorter and less tumultuous affair in some ways because my friends and I weren't living through it. So for us, this has been one extended affair that just goes on and on even though we live in the suburbs and our lives aren't affected by it. And and when we think of the civil rights movement, we think of these kind of spikes of bad things like, oh yeah, Emmett Till, that was that was really bad, but that was, you know, that was one thing. Or assassination of Martin Martin Luther King Junior, yeah, that was just kind of one event. It's kind of like, we view things in these one off events that are bad in and of themselves, but we don't feel the weight of just years and years of this piling up.

Derek:Whereas the events that we're experiencing here, you know, in some ways aren't aren't as bad and and oppressive as we might think of it in the civil rights movement, but we feel the weight of just this continuation of things pressing down on us. And that brings us to the second point. Events are often judged differently when our lives are disrupted. Now, we know the outcome of the civil rights movement, and we can cut through the bias much better now that we're sixty years out. We can clearly see who was good and who was evil, or at least most of us can though.

Derek:I'm realizing there's a segment of the population, a larger segment than I thought, who might not be able to clearly see who was good and evil. We can recognize the oppression of blacks and the justification of their displeasure in retrospect. Like, it makes sense to us that that Jim Crow was was horrible and what was going on was terrible. Like, we can see that sixty years out. But when we're in the system, it's not only harder to identify wrongs because we're likely the ones blindly perpetuating the wrongs through direct action or through ignorance, but also, we're less likely to want civil action because protests impact our lives and feelings of security, and legislation would impact our current way of life.

Derek:We don't want the cost of change. Because let's be honest, if we're not part of the oppressed group, we probably in some ways are benefiting from the oppression of that group, in some ways, whether that's, you know, some of us a lot more than others, and some of us maybe not at all, but in general, probably we are. And certainly when talking about actions towards reconciliation, almost everybody would be impacted. We're self interested creatures, you just ask somebody about voting, and it's about their pocketbook, and it's about they'll find, especially if they're Christians, they'll find a million ways to try to say that it's not about their pocketbook, but there's a lot that's about their pocketbook, and abortion's a convenient way to protect their pocketbook, you know? Being a one issue voter means that they can protect their pocketbook without thinking, because most people I know who vote Republican are benefited much better from voting Republican.

Derek:And I've specifically, if you've listened to previous episodes, I've had churches and individuals basically try to justify Trump and the Republican Party in large part economically. And they might be right about the economics, okay? Let's give them that. But when you try to justify moral behavior, moral acts based on economics and outcome for yourself or for a group, I just you can't justify morality that way. So, a lot of us are very self interested, even and especially Christians.

Derek:And because we're self interested, we have all kinds of defense mechanisms to avoid recognizing the plight of the oppressed. My friend, despite being upstanding and godly showed in this instance how our natural tendencies and perceptions shape reality for us a lot of times. The third and final thing that I want to say as we prepare to go into this discussion is that the interaction with my friend showed that a lack of historical context skewed his perception. And this this isn't a jab at him at all. This is true of most of us, most of the time, myself included.

Derek:It's easy for us to look back and see the oppression of blacks in The United States and understand why they'd want change in the sixties. But that wasn't so easy for many white people to understand in the sixties until images like those of Emmett Till showed up on the news. The groups who don't experience oppression often require a jolt out of their slumber because if life is peaceful for them, they can imagine it's not good for everyone else too. And if it's not good for everyone else, it's probably their fault, isn't it? In America, we're self made individuals and if your life is garbage, then you probably made that garbage for yourself.

Derek:Just pull yourself up by your bootstraps, right? My friend's life was great, and because most of his friends and coworkers are white, and the few who are black are in basically in the same socioeconomic situation, and even if they weren't, no black person is going to unload their baggage on him in such an environment. He just couldn't understand why all of these protests were coming out of the blue, and why they were persisting. I mean, life is better than it was in the 50s, isn't it? We passed legislation in the 60s and Black people have been silent about things for fifty years, and now they want to come and complain about it?

Derek:He just didn't get it. Being ignorant of Black literature and discussions throughout the century makes it easy for white people like me, and my friend, and those in my group, to dismiss the current tension as a fad. Why can't they have a solid meaningful platform like King did? We ask. Instead of reading and understanding the literature and recognizing that this current movement is an extension of King's that has been bubbling under the surface for decades, we dismiss the movement as opportunistic and shallow.

Derek:I was at a protest with the AND Campaign last year, or maybe it wasn't a protest, I don't know. I don't know what it was called, a worship service, a meeting, something. And one of the things that the speaker said really made me tear up, and he said it so well, I'm sure you can probably find it, it was like summer of twenty twenty, but he recounted a conversation with his mom where he asked her why she stopped her advocacy. Why didn't she keep on fighting? And she answered him, she said, I got I just got tired.

Derek:So very tired. After decades of de facto slavery as sharecroppers, fear of lynching, retaliation for attempts to migrate out of the South, housing discrimination, fire bombings when you moved into houses, loan discrimination, I mean, all kinds of things. When civil rights legislations ended up being passed in the late sixties, so many blacks felt the way that this man's mother did. They had seen and experienced so much torturous hardship, terrible hardship, and outright oppression, that despite a society that was still against them in a lot of ways, in a society that wasn't racially healed, as the Kerner Commission, the Kerner Report showed in '68, I mean, very clearly that things weren't resolved. Now, blacks were like, whatever, we're just so tired and we're in a better situation than we were.

Derek:Let's just take it. Take the money and run. They had gained enough grounds and they could kind of rest to a certain extent. With King dead, it was all too easy to settle into a better, though not equal life, for sure. So whether you hear the words of Du Bois in his The Souls of Black Folk, you listen to the eloquent words of James Baldwin, or you read the Kerner Report about the the true deep seated race issues, or you look at the progression of critical race theory today and where it came from, you're gonna see common threads from way back in the day, you know, with Dubois, Dubois, I've heard it said both ways, not sure.

Derek:But, yeah, you're gonna see this common thread from way back in the day all through today. This isn't something that's come out of the blue. Ferguson didn't spark a new fire. It was a fire started on the embers of old which hadn't yet died out, and it was easily stoked as the fuel of more and more black lives were thrown onto it. The point of this is that, as I discussed the civil rights movement today, this is a snapshot of a very long standing issue.

Derek:We are we are downstream in this river. The current has brought us to this point in history, but we are not in we are in a current of the river, right? This is a continuous current, this isn't something that's come out of the blue. There's so much backstory to understand leading up to the civil rights movement, there's so much to read about from then until now. I'll post a bunch of suggestions in the show notes below.

Derek:I've done a ton of reading on black history and and reading from great black minds in the in the past year and a half. So I'll I'll put some of my favorite favorites down there, but understanding history is really, really vital to understanding what goes on in the civil rights movement, particularly for US citizens, and particularly for white US citizens in suburbia. I understand this is a long introduction to the issue proper, but I think it's an important one for those for those of us here in The US. It's too easy to look at the civil rights movement as this short, unique event rather than a drawn out event that came out of something and led to something else. As we've discussed legislation in our Means and End series, and as I'll be revisiting issues of the government in a future series, laying out this understanding of the movement is going to be vital.

Derek:It's also vital to understand for those looking to build bridges between races and to seek reconciliation. If we view the civil rights era as some unique island, some panacea, you know, resolved in '68 through legislation for the black community, we fail to understand the whole story, then we're gonna severely misjudge our current situation. We're gonna severely misjudge what appropriate strategies are for fixing race relations. And most importantly, we're gonna misunderstand our black brothers and sisters who have been screaming for centuries, and in many ways, have yet to be heard. Alrighty then.

Derek:Let's let's move on into the issue proper. I think the first thing that has to be acknowledged about the civil rights movement when coming from the standpoint of non violence is that the movement wasn't inherently non violent. There were quite a number of people who advocated violence or at least armed resistance during this time. The Black Panther Party obviously came about during this time, but you also see individuals like Robert F. Williams, who who came to prominence.

Derek:I was introduced to Williams when I I read his book Negroes with Guns, and I didn't realize what a big influence he was at the time until just recently when I was researching the civil rights movement in more depth. Apparently, he had influences on the likes of people like Rosa Parks, right? This lady this lady who kicked off what we know as the non violent aspect of the civil rights movement with her refusal to move on a bus, and she was influenced by this guy who advocated violence. That's kinda interesting. And there there are even quite a few people who credit Williams with setting the stage for a successful non violent movement, even though he himself was violent.

Derek:They argue that it was when Williams and his followers showed a willingness to resist, as as his book says, with guns, that whites began to realize, hey, we're not gonna get free shots in at the blacks. They're gonna do something back. They've got power. Understanding that whites could no longer do violence towards blacks with impunity, the nonviolent aspect of the movement was able to progress without being immediately crushed by Whites. This perspective is interesting and it is very possible.

Derek:We've discussed before how every set of circumstances is unique, and surely there are outside influences that determine strategies that will or will not work, and the effectiveness of nonviolence. So it's very possible that this explanation holds merit. It might help to explain not only the power of the nonviolent movement, but how it was able to accomplish its goals so quickly. Fifteen years is pretty quick for for such a huge, huge impact. And there really is no denying this possibility, and non violent movements, like I said, often do have outside factors that contribute to success.

Derek:However, hopefully this series helps you to see that there's a trend with non violent movements, even with other variables controlled. And by the end of this series, you're going to have so many different stories, and this is just scratching the surface of stories. So many stories, and then Why Civil Resistance Works, the research book that kind of gives you gives you data that I think you're going to see, okay, well maybe Williams was importance for the the civil rights movement to work non violently, but nevertheless, that doesn't mean that non violence doesn't work. It's just it was able to work in a unique fashion in this way, and use strategies that it might not have been able to use in other situations like, say, Apartheid South Africa. Despite the violent tendrils that wove their way through the civil rights movement, the core of the movement was nonviolent.

Derek:And we can't forget that it is nonviolence that allowed the movement to gain the numbers that it otherwise wouldn't have had. And with numbers and diversity, recognition and impact grew significantly. Williams by himself, how much much of an impact would he have had, his group? How many people would have taken up arms? Would would they have had enough force to be able to do that?

Derek:What would society's view have been if all of a sudden black people just start shooting White people, and of course, people are going to flip the narrative that they're being attacked by Black people? We already get enough of that today, right, with like with viewing in our culture, viewing Black people as more dangerous, right? So what might that have been like if the black movement was violent? I don't know. Right?

Derek:The violent people love to play the hypothetical game. But hypotheticals, as as we continue to see throughout this podcast, can work both ways. But beyond those who advocated violence, there were also a large number of nonviolent activists who only embraced nonviolence as the best strategy at the time. They weren't committed to nonviolence in principle, but recognized that their situation was best suited for nonviolent activism. So they were opportunistically nonviolence.

Derek:While this set of circumstances could undermine the civil rights movement as a notch in the belt or a feather in the cap for nonviolence, I think it can actually help it in some ways. So if nonviolence works with those who are only committed at a pragmatic level and aren't really true believers, and and they aren't really nonviolent at heart. What might nonviolence look like if implemented from the core of a group's being? Nevertheless, the civil rights protesters did have something arguably group had before. Maybe maybe Gandhi's group, I don't know how well trained they were.

Derek:But in the civil rights era, you start to get people who are strategically trained in non violence. Now Gandhi did have a strategy, right? We called it satyagraha or something like that, soul force. But Gandhi's movement was really kind of the first of its kind, you know, to be so well thought through. It's one of the first mass movements of its kind that had a leader who's really thinking non violently.

Derek:And a lot of the people who ended up participating weren't trained. And as we saw in antiquity or in the American Revolution, non violence was used throughout history, but people weren't trained, it was more spontaneous. But after Gandhi, King had time to study his movement, and they recognized the importance of training people in non violence. So they actually started training. SNCC, I believe, came out of this, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Commission, something like that, I don't remember what it stands for.

Derek:But you had you had that movement and there are people who are training, like the Freedom Riders and stuff, training what does it look like to embrace this ethos of of non violence. And you didn't have people who are trained like that before, to such a degree. I've said it before but I'll say it again, when you consider that the US military has been in service for over two hundred years and it gets a huge, huge, massive chunk of funding from our our budget and they're able to weed out the, you know, the recruits that they don't want, and they get only the best. And then you compare that to non violence, which largely anyone can attach themselves to at will. They tend to have very little funding and very little training by and large, and it's just, it's amazing that the success of non violent movements is so high and the US military has so much waste and inefficiency.

Derek:So comparing violence to non violence is just it's incomparable. It's apples and oranges. I mean, violence is behind on every measure, and nobody would ever expect it to succeed like I never did until I actually started looking into it. But in the civil rights movement, this is where you just start to see people getting a little tiny bit of training, and kind of making this act, non violence, that is already effective as we saw with Gandhi and colonial United States not against Nazi Germany, and now you're finally getting people who are being trained to do it, and maybe even gonna be able to make this more efficient, which we do see throughout the twentieth century that non violent actions tended towards becoming more efficient, producing better results. There are a number of powerful stories that we could tell about the nonviolent movement here, and how training and patience really paid off.

Derek:King getting hit in the head with a rock while in Chicago and not retaliating, or him taking a punch at a meeting with the assailant and then meeting with the assailant afterwards are two that come to mind. But, you know, I I really I have talked about King throughout this podcast, so I'm actually trying to kind of avoid talking about him, not because that's a bad thing, but I I think so much gets placed on his shoulders that we don't branch out and see the stories of other people, or we just see him as kind of the non violent figurehead and, you know, other people as kind of lackeys who are just tacked onto it. So I'll tell you just one brief story of of this guy, Andrew Young, from an article that I'm gonna put in the show notes. Now, Young wasn't ideologically committed to non violence, but he tells a story of how he came to realize the power of non violence, not only to be more effective in the short run, but in the long run as well. So here's a a an extended quote from the article.

Derek:Quote, can I just have one story right quick? When Martin went to jail with Ralph Abernathy in Albany, Georgia, I'd never been involved in the movement. I just got there, and I had to go in and see him every day. So I go in there and there's this big sergeant behind the desk who was white, and I said, excuse me, sir. I'd like to see Doctor.

Derek:Cain. He didn't even look up. He said, a little nigger out there wants to see them big niggers back there. What do I do? I said, oh, shucks.

Derek:They said, send him back. So I went back. And I told Martin and Ralph, you know what he said to me? Martin said, I don't care what he said to you. You got to get in here every day and give me a report on what's going on.

Derek:Ralph said, Why don't you jump across the desk and slap him? I said, He's bigger than me and he's got a stick and a gun. It just took that to bring to, bring me to my senses when I went back out. I said, Wait a minute. If I go to come in here every day, I saw his name and I said, Thank you very much, sir, Sergeant Hamilton, I'll see you tomorrow.

Derek:And I left. When I came back in the next day, I said, Sergeant Hamilton, how are you doing today? And I said, You must have played football somewhere. And he sat up, and we'd start. He went to Valdosta State, played tackle.

Derek:We talked about football for about three minutes, and I said, Can I see Doctor? King? Yeah, go on back. See? When I came when I came back out, I mean, every day like that for about ten days, it didn't take but two minutes, just calling his name, and we became friends rather than police and scared Negro.

Derek:Long story short, I go to the UN and I'm up in Maine speaking, and who comes up to see me? But this tall, no longer fat, tall and skinny, got a green jacket with white pants and white black white buck shoes. I mean, a New England playboy. And he comes up and says, you don't remember me, do you? I said, where did we meet?

Derek:He said, Albany Jail. I said, He said, I'm Sergeant Hamilton. I said, what are you doing up here? He said, as soon as you left, I realized that I didn't want my children to grow up that way. And I put them all in the back of my station wagon and I found a job up here as a security guard.

Derek:And I said, well, how are your kids doing now? He said, they're in some of the finer schools in New England and I just came here tonight to thank you. Now I can probably find, you know, several hundred situations like that. Now, I didn't come for non violence, I just ended up in the middle of this. But I mean, I've never been in any play, in any situation where violence would have helped me more than thoughtful non violence.

Derek:End quote. So as Young says, there are likely hundreds, if not thousands of similar stories we could pull out just from the civil rights movement that that work out just the same way. It's the type of thing that you're gonna find over and over again, whether it's with non violence against the Nazis or the neo Nazis. A fantastic movie that that depicts this kind of change, but which also depicts the tragedy of cyclical violence is is a movie entitled American History X. I don't necessarily recommend that you watch it.

Derek:It has quite a few graphic scenes which are are pretty harsh, but it's a really powerful, moving, and tragic film. It shows how how love can change even enemies. From Frederick Douglass to Martin Luther King Junior, many who have been oppressed recognize that their oppressors are themselves oppressed by their hatred and ideologies. Hatred and violence won't free them from that or break the cycle, neither will legislation. Loving and treating an enemy as a human are wonderful ways to break through hatred.

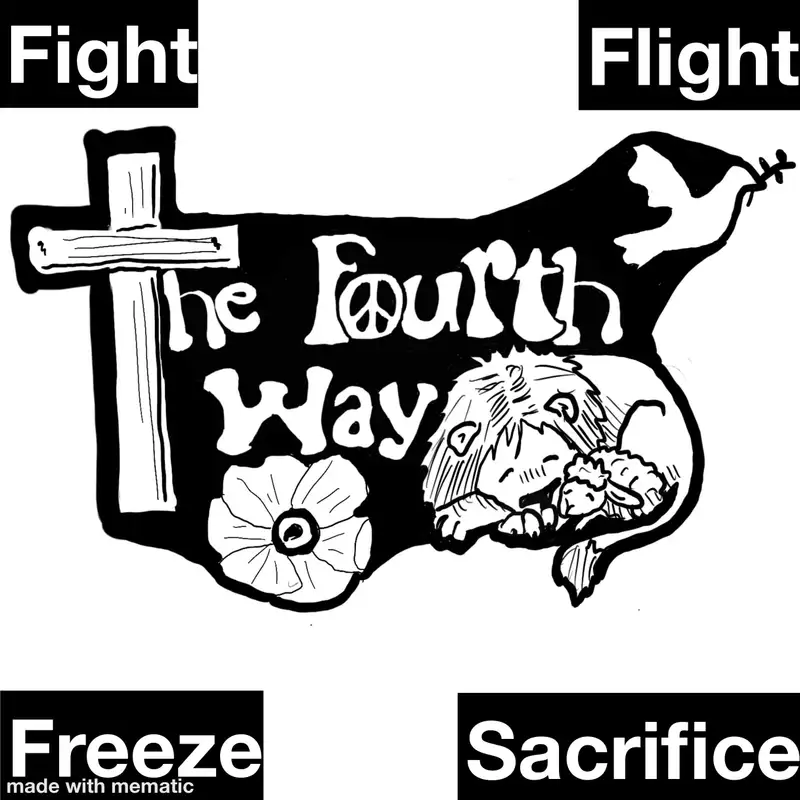

Derek:It's what Jesus is getting at when He tells us to turn the other cheek, to give the clothes off of our back, or to go the extra mile. And Walter Wink has a great essay on this, something like Jesus and A Third Way, where he talks about what Jesus is getting at here. When we turn the other cheek or give the clothes off our back or go the extra mile, we not only expose the evil being done towards us, but we also humanize the objectifier. And that's what I think we see in Young's story in the Albany Jail. He humanized an oppressor and he allowed the oppressor to see his own humanity.

Derek:Another one of my favorite stories of redemption is that of George Wallace, which unfortunately, you don't ever hear too much about. You hear about Wallace's terrible, terrible days, and how horrible he was, and he was. He was a staunch segregationist and he was known for saying, Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever. But in 1972, there was an assassination attempt on Wallace's life, and in the pain of that moment when his life was changed forever, he was paralyzed, Wallace was visited by some who should have been his bitter enemy, and he was forgiven over the next few decades as he sought forgiveness by a number of people that he wronged, wronged very badly. And of course, we can question his sincerity and a lot of people do, but regardless of his reasons, it's quite the turnaround to hate black people and then humbly confess your sins to them over decades.

Derek:But, you know, we shouldn't be so skeptical about Wallace because we have modern stories like those of Daryl Davis, a black man who has converted directly or indirectly over 200 KKK members through loving them in conversation. We know the power of love and the possibility of transformation for the wicked. And especially if you're a Christian like me, we have to know this from firsthand experience. If we truly believe what the Bible says about the depths of our own sin and the measure of God's love. But the civil rights movement doesn't just have individual stories like these of the power of putting evil on display.

Derek:I think one of the things that I I would pull out as maybe not unique to the civil rights movement, but something that stands out very clearly is that it shows us what we perceive as the power of innocence, especially the innocence of children. Some of the biggest incidents and catalysts in the movement were centered around children. Brown versus the Board of Education was about kids and getting quality education, equal education. We see Ruby Bridges, this young innocent girl going to school and just the vitriol on the people's faces and the terrible things that they're saying and doing. We have the church bombing that killed several little girls.

Derek:Emmett Till's open casket funeral, college kids being killed on their freedom ride, little kids being arrested and hosed and and, having dogs sicked on them. The involvement of children in this movement, in my opinion, was huge in exposing the evils of segregation and racism. While some of these incidents would have occurred without non violence, non violence provided credibility. Had Emmett Till been a street fighter who was attacking racist whites, would his open casket have impacted the nation like it did? I don't think so.

Derek:Would an open casket of a kid who was doing drugs or who was gang affiliated impact the broader society today with all their prejudices? No. It should, but it wouldn't. When one is associated with violence, note here, associated with it, don't even have to do it directly, it often discredits them. It makes whatever violence is done to them simply just desserts, especially if you're talking to somebody who just wants an excuse to dismiss their life.

Derek:It negates our ability to empathize with them because they're not innocent anymore, they're a combatant. I think the civil rights movement capitalized, whether knowingly or unknowingly, on this idea of innocence. Not only innocence and remaining non violent and therefore undeserving of the violence meted out on them, but also this innocence of childlikeness because they were literally children. While all humans are invaluable and are created in the image of God, seeing violence and hatred directed at children just stirs something up in most of us intuitively. You only get that innocence and that advantage when you have a non violent movement because it not only incorporates kids more readily, but it also allows them to maintain their perceived innocence through nonviolence.

Derek:Now I do want to say something here because you might think, Well, that's horrible that we would include kids in such movements. But we saw this even back to the Jews in antiquity, they had their whole families with them. When we see in Colonial America that girl who threw tea out the window when she was with the governor, you see children involved a lot, and, we're not talking about child soldiers here, you're not having children go and do this morally questionable stuff. And certainly, we get into indoctrination and forcing kids to be a part of a crowd and using them as human shields, that's not what I'm talking about here. What you see in these movements, especially in the civil rights movement with the children who went out and protested is that they recognize what's going on in their lives.

Derek:We're not talking about like three year olds going out and protesting, mean, don't know of three year olds going out to protest, but you're talking about children who are making a decision and maybe you say, Well, they're not informed enough to make those kinds of decisions, but you can't forget that their lives are impacted. When you have Black kids who are taken to jail without their parents knowing about it, or who are lynched for kissing a childhood friend on the cheek or whatever when they see each other for the first time in years, or sending them a postcard, a Christmas card or something. Like, kids recognize at a pretty early age what's going on. And I saw this when I was at the AND Campaign Rally too, where they were talking about having their kids at these sorts of events, like they're recognizing what's going on. Like when you do that, I think they were doing the nine minute remembrance for George Floyd, I think that's what it was, taking a knee.

Derek:And their kids, pretty young kids, were involved in that. And recognizing this is the world that you live in, you need to be careful. I don't think it's fair that kids at a pretty young age can reap the consequences of a racist society, particularly back in the 60s, and then say that it's not right for them to be able to participate in these sorts of events. So I recognize that there can be some kind of line here where you exploit children in nonviolent movements, and I'm not talking about exploiting children. That could be a whole another show, we could have a whole discussion on what it looks like to have children reasonably participate at what age, what type of process would be exploiting them, what wouldn't.

Derek:But all that aside, I think what you see in the civil rights movement is kids making meaningful choices, knowing the consequences, and just recognizing consequences of not participating in those sorts of things. They see what happens to their parents, they see what happens to their older friends, and I think it was legitimate. And it was huge, it had a huge impact the public perception of what was going on. All right, so now I want to move on to before we end the episode, to recognize one issue that I think can arise when we discuss nonviolence. King had to deal with a number of cynics who were rightfully upset because it didn't seem fair to them that they had violence done against them, yet they were expected to be nonviolent themselves.

Derek:And we see this double standard still today. We destroyed property, Americans destroyed property in the Boston Tea Party, but that was okay, because it was for a just cause, right? We had taxation without representation and started the Revolutionary War, but that was okay because we were justified. Yet, when the blacks are taxed and underrepresented for a century or more, their riots and their inhum are are inhumane and uncivilized and uncalled for and unjust. Whites started all sorts of race riots, yet when the Blacks lashed out from their pent up frustration, it's abhorrent.

Derek:To many blacks and to many oppressed groups, non violence can seem like a tool of the oppressor. And that's what we see with the Black Panther movement and through people like Malcolm X. He wasn't particularly violent, but we see that he parted ways with King and what he saw as capitulation to this double standard. And there's there's still a huge rift in in this regard today. If violence didn't seal the deal in the sixties, and if whites only started noticing the modern problem after people started breaking and burning things, then maybe non violence isn't the answer.

Derek:Maybe violence is necessary to be heard. That's not something that I can make the case against from the civil rights movement alone. But I'm hopeful that understanding the Christian basis for non violence from love, and by seeing the broader perspective of non violence through various movements, that that's gonna give a glimpse of how nonviolent action has worked and where it has failed. And I'm also hopeful that you won't see my advocacy for nonviolence as a tool of the oppressor because as the Christian, we should be bearing our crosses. And I'm gonna have an episode about that a little bit later because I think one of the things that tends to undermine what we ask people to do, we ask certain groups to sacrifice things when we ourselves are unwilling to sacrifice, and that is a double standard.

Derek:And so I do understand this complaint, but it is just something that, like I said, we'll get to later, but the complaint arises not because it's nonviolence is untrue, but because Christians are hypocrites, and it's something that we are unwilling to bear our crosses about. And unfortunately, we've been some of the biggest oppressors. And that's also why many true Christians have been persecuted throughout history, because true Christians are seen as a threat to fake Christians. In the end of the civil rights movement here, I think we end up seeing as a result of nonviolence, even though it did accomplish a number of things, we do ultimately see that that it failed. It didn't seal the deal.

Derek:It didn't get what people thought they got. We realize from the civil rights movement that legislation is a really low bar to accept as success. As that individual at the AND campaign said, you know, to his mom, Why didn't you keep fighting the fight? As our episode on CRT talked about, and how legislation really didn't seem to be the advancement that people thought it was. Yeah, legislation is a low bar, and the civil rights movement didn't accomplish what most people think it did.

Derek:And in fact, talking with my Christian friends and churches and supporters and things, I mean, in some ways it's been harmful because what when when you have protests today and discussions today, what's the conversation that I hear? Well, it's not like it was in the fifties, right? We passed legislation, so it's better now. And legislation, this legislation that was passed, is now the proof that racism and racial injustice don't exist today. It's a scapegoat.

Derek:And why is it that legislation is a low bar oftentimes? Well, we can see that oftentimes legislation that is implemented by those who are in power is meaningless legislation, because the people in power usually aren't going to implement things that are harmful for them. And again, go back to the CRT episode that we had in the last season on Means and Ends, where we talk about legislation. Second, the people who implement legislation often implement counter legislation to replace the new legislation. So if you're going to be able to have Blacks start to vote, what happens within the next couple years?

Derek:Like now that Blacks can actually vote and we take away, you know, literacy tests and all that kind of stuff, while we see voter disenfranchisement come through the back door with our war on drugs, and we see the the black incarceration rates just skyrocket. So all kinds of policies come in that end up hurting the Black community, sort of as as counter policies, counter legislation to this legislation that was implemented. If you didn't want Blacks to vote before, you can set up meaningless laws that make it look like you're you're helping black people vote, or you can set up laws that help black people vote, and then just disenfranchise them in other ways. You just you do a cursory look through history, and it doesn't take you very long to uncover those sorts of things, both of those things. And then of course, third, legislation doesn't reconcile, it doesn't change hearts, it doesn't it doesn't fix what's there.

Derek:And even if you think that legislation puts a band aid on a problem, you just think back to back to the last two points we just said, right? Legislation is oftentimes either meaningless, or it's countered with other legislation. Again, another example, sharecropping, right? Okay, well, slavery's gone, but no, it's not really. Just read a read a book called The Warmth of Other Suns, and blew my mind open about even like the Great Migration and how sharecroppers are slaves.

Derek:Like, they were slaves. They were tied to basically their owners. He wasn't their owner, but they were. They pretty much the majority of them didn't get any wages because their owners kept the books, and of course, the Black people were always indebted to them and never got any wages from them. And if they tried to move away, they were sometimes lynched, or they were beaten, or whatever else, like they couldn't move even if they wanted to.

Derek:It's just insane. So, okay, we can get rid of slavery and we just implement some counter legislation. So legislation is a low bar because it doesn't get issues, it doesn't fix things. And especially today with our church being so focused on politics and legislation, that's a problem because legislation is really just the lowest bar you can reach for. We talk about preaching the Gospel and how important that is, but we don't.

Derek:We don't live the Gospel. Maybe we say the word Gospel a lot and we say the word Jesus a lot, but we don't live the Gospel. And again, we're going to have an episode on that as well, but you know, legislation just does not change hearts. You hear that over and over in this podcast when we talk about Romans 13, when all over the place. I've said before, say it again.

Derek:Legislation doesn't change hearts, it's a low, low, low bar. It's like the speaker at the end campaign rally said, his parents' generation stopped too soon. They didn't finish the fight because they at least in part thought that the fight had progressed sufficiently because it ended with some good legislation. But as we've seen over the past five years, our nation has a huge racial divide and we have a group who who sees that and is ready to fight again to pick up the torch that their parents put down for a time. I'm sure I could go down a number of other rabbit trails and such, but I'll close things down here, I suppose.

Derek:Again, I know this might not have been what you were expecting with the civil rights episode, we didn't get into a lot of civil rights specifics. We just kind of pulled out some of the things that I thought were were most important that that we see in the civil rights movement that are emphasized maybe more than in other movements. And some important stuff for for those who are US citizens trying to comprehend this this racial divide. I will put a ton of resources in the show notes for you to check out. I don't know exactly what I'm gonna put in yet, all, but it's probably gonna be the most heavily sourced show yet because I want to put a lot of the racial the books that have helped me to understand racism and the race issues more historically.

Derek:Yeah, so I'll try to do that. So you have because reconciliation is important, and non violent action generally tends to seek a change in legislation, which we'll talk about later, but reconciliation is the most important. So I want you to learn about that, the history so that you can be a reconciler, not just somebody who seeks to change legislation. Well, that's all for now. So peace, and because I'm a pacifist, when I say it, I mean it.