(105) S7E2 Nonviolent Action: Reasons Why Civil Resistance Works

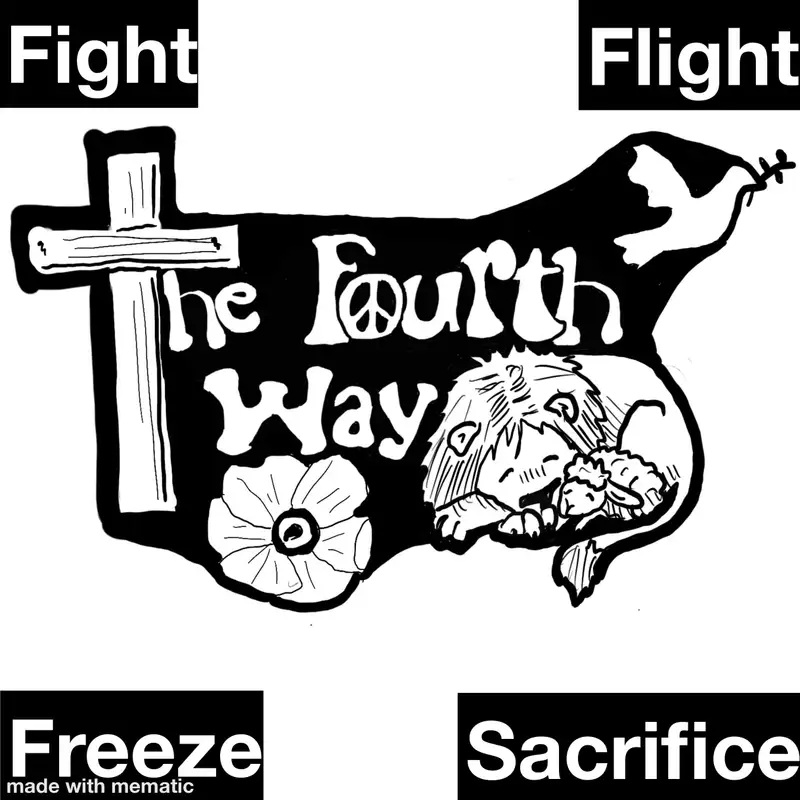

Welcome back to the Fourth Way podcast. Today, we are continuing our discussion on nonviolent action. In the first episode in the series, I laid out a more primal foundation for us in focusing on what tends to drive our response to threat and confrontation. We are often driven by fear. We discussed how fear is usually viewed as a driving response of flight, but that a lot of times, we don't really consider it a driving force in the fight response.

Derek:But when we reflect upon this further, we know that fight can definitely be a fear response. We recognize that in animals, when they're scared, lot of times they can react by running and cowering but they can also react by fighting and attacking. We also see this in humans. So I had a friend in college and I loved to scare people. We lived up on the second story and so there's this door, it was like this largely wooden door and it had just a little slit that you could see through.

Derek:But I would crouch down when my friends were coming up the stairs because I knew when they'd get back from work and stuff. And so that I would crouch down and then when they opened the door, I'd pop up and I'd be like right in front of their face and I'd I'd yell. And I had this one friend, Chester Frank Dudic the third who is who is now a children's author. But what he would get scared more easily than some of the other people and I remember this one time he was coming back from work and I got him really good. He was just kinda out of it, I don't know, listening to music or singing or something.

Derek:And when I popped up, his face looked so scared and he kinda reeled back a little bit, but he immediately like stuck out his hand and just he he stopped himself from punching me but he like slapped me in the face. And it was just, it was his natural reaction from being scared. He just, he just slapped me in the face. It was hilarious. But fighting can definitely be a natural response to fear.

Derek:And I think you can extrapolate that out further, you can extend it, you know, when it's fear in the moment like it was for my friend or maybe for dogs or some animal that's fearful. But we could extend that out to being fearful for one's future, being fearful for one's children. So it's not necessarily even just a momentary thing. Fear causes us to be willing to do violence to others. Even if you're talking about, you know, politics, fear for the economy might cause me to vote a certain way towards other groups of people that I might otherwise choose to help but not at a cost to me.

Derek:So fear is a is a driving force against violence, whether that's violence of going and shooting somebody or going to war or whether that's other sorts of violence that we do in our society. Fear is at the root of a lot of of action. We also discussed what the opposite to fear driven response might be. And as the fourth way, we here determine that this response tends to be self sacrifice as opposed to the sacrifice of others. To choose sacrifice or a willingness to sacrifice is to count one's life as lost and to face fear head on without weapons and in seeking the good not only of oneself but of others.

Derek:Now don't get me wrong, if you don't have to sacrifice, you know, you don't have to die in a particular situation, that's ideal and the non violent person doesn't want to offer themself up as some human sacrifice. That's not the end goal. But there's a willingness to have that occur in the process of doing what is the most loving. So we are willing to make ourselves vulnerable. As Christians, the reason behind this is more than an attempt to be pragmatic, though I think, I mean, we can discuss how it is pragmatic a lot of times, but it's a response which is driven for Christian, for those who are non violent Christians, it's driven by enemy love and ultimately love for our Savior, but because our Savior shows us what love truly is, it drives us to have enemy love as well.

Derek:We will make ourselves vulnerable and be willing to sacrifice because we love our enemies as Christ has loved us when we were His enemies, and we refuse to seek our ends using means which intend to harm others. Now, in my experience, a lot of people tend to be dismissive in the conversation up to this point. It doesn't matter if you're a Christian or a non Christian, you likely don't care about the moral rationale behind non violent action. Logic, morality and history don't matter too much to people when discussing weighty issues of life and death. And sadly, that's even true of Christians.

Derek:And we might say that we like morality, but honestly, we're pretty dismissive of morality that doesn't work out too well for us. And you can go back and hear me talk about that through the seasons, particularly in the consequentialist season, we turn things into metaphors and we make things easy that we don't like and the sins that we tend to be the most critical of are the sins that we don't really ever have to worry about experiencing ourselves as our group. So while you'll never hear gluttony preached about or rarely ever, even though that's one of the seven deadly sins, but you will hear something like socialism railed against by conservative Christians. I mean, it yeah. Anyway, I can get on rabbit trails and go off on that too easily, but that's not the point here.

Derek:Ultimately, people want to know what works. That's the point. And let's be honest, taking up arms to fight an aggressor seems like it would be a lot more effective than showing up in the public square vulnerable and without any weapons. So, we are going to get into the practicality of non violence right now in this episode. However, I I do have to preface this by saying it's a bittersweet moment for me because if you've listened to season two, you understand that I I despise consequentialism.

Derek:I despise this idea of the ends justifying the means. And that's such a common ethic in our society and even and especially among Christians who tout moral objectivity, I mean, it's just a problem everywhere. We Christians say that we don't adhere to consequentialism, but I mean functionally, we do. We do all over the place. So I recognize that the danger of doing a season like this is that it might be divorced from Biblical and moral grounding.

Derek:Any non Christian could listen to this series and simply be convinced that non violent methods work without any need for Jesus. And while I think that that would still be great result and it would make for a better world than where people go around killing each other to resolve problems, it would be missing quite a lot. Like the deep grounding of enemy love which makes non violence not only a practical strategy but a compelling one and a moral one. That's what gives it its moral objectivity or it's at its core, this idea of love. So in this series and especially in this episode, I absolutely don't want to be heard as saying that non violence is right because it works.

Derek:That's not how objective morality works. If non violence is the morally right way, then it ought to be implemented whether it works or not. But here's the thing, so at the same time that I am not a consequentialist, and I think that's a huge problem for Christian ethics, at the same time, I believe that God created the world to function properly and in accordance with His character and will. So it makes sense to me that living a life of sin tends to bear out its own natural consequences apart from any direct, divine or governmental intervention. Sin just naturally leads to death.

Derek:Adultery, promiscuity, anger and all of those other sins tend to lead towards broken lives, diseases, whether that's STDs or heart disease or other stress related issues. A sinful life or a life not lived morally or appropriately tends to lead towards more turmoil. And that's not a health and wealth gospel, like if you just do the right thing, everything's gonna go well, of course not. But in a world that a good God created, not adhering to the types of things that align with His character tend to not produce good results. So in such a world, a world where a loving God created everything, its laws and all the matter and everything, I would imagine that something like non violence would prove itself to be better functionally, pragmatically.

Derek:And notice that I am not saying non violence is good because it works. I've said that like three times already, but I need to say it over and over again. Non violence would not be good just because it worked, but rather, we'd be saying that non violence works because it's good and the world that God created was good and works accordingly. I believe it was Martin Luther King Jr. Who said something to the extent of like, Justice is woven into the fabric of the universe or something like that.

Derek:And that's kind of what I'm saying here. God is a good God and things tend towards correction. So Israel, when they are living lives of absolute immorality and idolatry, they get conquered and taken into captivity. God's universe has a way of eventually punishing the wicked even if God doesn't do that directly by His hands. The laws of nature, the laws of objective morality tend to work that out in and of themselves.

Derek:So if we find out that non violence is very practical, that shouldn't be shocking to us when we think about it, as Christians anyway. Though I know that that will be shocking to a lot of people who are just starting down this path of non violence because it seems counterintuitive. So even though I'm a little bit hesitant about this season because I know that somebody out there, more than one somebody out there is going to misunderstand or misquote me. I'm also excited about it because if you don't take it out of context, this is a beautiful thing that I think points to the wonder of a good God and specifically, to the wonder and beauty and love of a God who Himself is non violent love as depicted on the cross. And this is the Gospel.

Derek:We love Him because He first loved us when we were His enemies. So with the Gospel in view, let's go ahead and start digging into the discussion of how non violent action might work. In this episode, we are going to look at the theory behind nonviolence, and then in the following episodes, we'll explore various nonviolent actions from the past and do some assessing, different assessments for them. For this episode, the main text I'm going to draw from is called Why Civil Resistance Works. Now there are a lot of very good books out there, some other books which dig into the functionality of non violent action.

Derek:Two big names in this are going be Walter Wink and Gene Sharp, and a lot of people in the non violent community know them. Wink is going to give you a specifically Christian perspective, whereas Sharp digs a lot more into the mechanisms of non violence. Ron Sider has also written at least one or two works which are more digestible. However, I'm going with Why Civil Resistance Works because it condenses the findings and presents the findings with a lot of good data. It's more research oriented and more of an overview.

Derek:Plus, it's a bit newer than Sharp and Wink's works are, and I think being able to have something that's newer will be a little bit more beneficial because it kind of incorporates some of at least some of Sharp's ideas in here. Another reason I like it is because the author, Erica Chenoweth, has a testimony in which her position, coming to non violence was a result of her looking at the data. It reminds me a lot of the book, what is it, Lee Strobel, Case for Christ, you know, he goes out to disprove it and ends up being converted. Well this is basically the same thing just for the non violent position. Chenoweth goes out, she looks, she's like, this is kind of crazy and then somebody challenges her to, Alright, compile the data and you figure it out.

Derek:You show me. And when she does, she's just dumbfounded that non violence blows violence out of the water. It gives me a little bit more faith when somebody is an advocate of the other position and changes. When we're talking about the resurrection of Jesus, we call that, we like enemy attestation. So to have enemy attestation is very meaningful.

Derek:Mean think about Saul converting and becoming Paul. So he used to kill Christians and now he's willing to be killed as a Christian. Like obviously, something happened. Even if you want to explain that away and say he's delusional, something happened in his life. Something substantive happened.

Derek:And he might be wrong about how he interprets that thing that happened, but something happened. So for those reasons, I'm going with Chenoweth's work right here. And she's supposed to come out with a new one I think at the end of twenty twenty which, yeah, okay, forgot. We're recording this for 2021, so she should have already come out with a book. I forget what it's called, but if I can find it, will link it in the show notes.

Derek:If you don't wanna read her book and you my, and you don't trust my summary per se, you you can find a TED Talk which I'll link in the show notes as well, where she gives like a fifteen minute talk that summarizes things. We're gonna dig a little bit deeper than I think she gets into. Nevertheless, it's a good talk. Alright, let's jump into the specifics here. What did Chenoweth find out that was so compelling to her to make her change her common sense position?

Derek:Well, she found out from her research that between 1900 and 02/2006, nonviolent actions were twice as likely to succeed as violent actions in most scenarios, with very few exceptions. So there were some specific scenarios where nonviolence didn't end up being better, But then in those cases, violence wasn't really good either. So it wasn't like violence blew nonviolence out of the water, it's like there are just some situations which are in general pretty hard. So she found that transitions which resulted from nonviolent actions were not only more likely to occur positively, but were also more durable and successful. So not only was nonviolence more likely to succeed, but it was more likely when it did succeed to end in democracy and it was also more likely to avoid falling back into conflict and civil war.

Derek:So the resolution was more permanent than it was after violent successes, initial violent successes. So those are the two main, the two big points. In summary, non violent actions were more likely not only to succeed in the short term, but they also facilitated much better long term results. So how does Chenoweth explain this? Two words really, I mean if we could sum this up in two words, people power.

Derek:It works because of people power. She notes a few important things. So first of all, no non violent campaign failed where 3.5% or more of the population was involved, and many succeeded with much, much smaller percentages of the population involved. Now, 3.5% doesn't sound like a ton, but that is quite a lot of people. In The United States, I think she says at least at the time, it's probably more now, but that would have translated to about 11,000,000 people.

Derek:So if you can get 11,000,000 people willing to stand up in The United States to some injustice or whatnot, then pretty much according to statistics, you can't fail. It's going to succeed. She also notes that no violent act, no violent campaign surpassed that number. There was no violent campaign like people rising up against their government that was able to accrue more than 3.5%, three point five % or more of the population. In fact, nonviolent participation on average had a four times larger group than violent actions.

Derek:Here's a quote from the book. Chenoweth says, The average nonviolent campaign has over 200,000 members, about 150,000 more active participants than the average violent campaign. A look at the 25 largest campaigns yield several immediate impressions. First, twenty of the largest campaigns have been non violent, whereas five have been violent. Second, of the non violent campaigns, 14 have been outright successes whereas among the five violent campaigns, only two have been successful.

Derek:So, that would be 70% of the nonviolent campaigns were successful and 40% of the violent campaigns. So in other words, among these massive campaigns, nonviolent campaigns have been much more likely to succeed than violent campaigns. So having masses of people is very important because the people that you see who are involved represent a lot more people than you actually see. So okay, if you have 3.5% of the population participating, they have families and friends and other people who are too timid who are likely behind that. So 3.5% of the population represents a much larger percent actually.

Derek:But why is it that non violent campaigns are able to gather on average a lot more participation? And this is a big question for the researchers because, you know, it seems like if I can pick up a gun, I'm gonna feel safer and better about joining a movement because I can defend myself than if I go out in the streets against a repressive regime where they can basically just come and take me and I've got no defense. You know, a lot of times, if I have a gun and I can kill people, I feel like I'm accomplishing something. When you're being non violent, a lot of times it feels like you're not accomplishing anything because people go to jail and you're left without any tangible results like dead bodies of your enemies. Well, what the researchers discover is that a big part of the numbers game which the non violent action is able to produce is because they hypothesize that there's a lower entry, there's lower barrier, lower cost of entry.

Derek:You don't need physical prowess or special skills to be non violent whereas a lot of times, you do in order to be violent. You need to be able to be physically in shape, to traverse landscape, to hide, to crouch down, to crawl, to be able to shoot a gun, you have to have certain skill set, you have to have materials like weapons. So there are a lot of requirements to be able to do something violently. So in general, the elderly aren't going to be included in violent movements. Young children are not going to be included in violent movements and a lot of women, especially mothers who have children to take care of, are not going to be included in violent movements.

Derek:Essentially what you have is you have, in violent movements, you limit your participation to essentially, healthy fifteen to fifty year olds, something like that. That's largely your participation and they're all going be males or most of them. So fifteen to fifty year old males who are able-bodied. Nonviolent campaigns which you see in a lot of different campaigns and civil rights comes to mind immediately where you had the children come out and march. But nonviolent campaigns, I mean you've got people from all over the spectrum, male, female, young, old, able-bodied, wheelchairs, crutches, it doesn't matter, anybody can participate and you don't need certain materials to be able to do so.

Derek:And this diverse representation is important, not only so you can get more people involved and have a larger presence, but because when you start to get different rungs of society, the tendrils of nonviolence start to weave into the depths of society. So you get a broader swath of people represented in a nonviolent movement but then you're also going to be able to have more of an impact in society. So if you get shopkeepers and bankers and like when you start going across the the class spectrum, that's going to be important if you're going to do economic sorts of actions and actions which are going to apply pressure to the state. So when you have shopkeepers, utility workers, factory workers, and bankers start rubbing shoulders, not only does that solidarity produce a lot of cohesion and meaning in their minds, but it also impacts how the state functions. And that combination is emotionally and practically scary to governments.

Derek:So in conclusion here, Chenoweth writes the following, it is often operationalized as a state's military and economic capacity, our findings demonstrate that power actually depends on the consent of the civilian population, consent that can be withdrawn and reassigned to more legitimate or more compelling parties. End quote. What Chenoweth writes here makes a lot of sense when you think about it. As Christians, I think we can add to the insight and intuition here. Doesn't it make sense that a willingness to sacrifice our lives without harming another would be more fruitful than using violence to get our way?

Derek:Doesn't it make sense that a people who love because we were loved while an enemy of God, doesn't it make sense that us doing the same thing might have a similar impact? Doesn't it make sense that this would stop the cyclical violence of the Lex Talionis, the same cyclical violence Jesus tried to tell us to stop two thousand years ago? Doesn't it make sense that involving even those who seem like the weakest parts of many societies like women, children, and the elderly, would create a more powerful movement with communal cohesion? Doesn't it make sense that governments fear those who don't buy into their system in a compelling fashion, and that we serve a savior who is killed by the state for doing the same thing? I mean, non violent action is the exact type of thing you'd expect to conclude from reading the New Testament.

Derek:It just makes sense that it works because it's seeking not just to get immediate results, but it seeks reconciliation and restoration. It seeks communal betterment which includes those in the opposition who you're not willing to offer as human sacrifices to the cause. So yeah, believe it or not, nonviolent action works and for Christians, that should make sense. But I understand at this point that such a thing, such a truth might still be a little bit intangible, abstract. So I'm looking forward to spending the next five to ten episodes, not sure how many it'll be, but sharing stories about specific non violent actions and kind of dissecting them along some of the the thoughts that we've mentioned here so far in in our season.

Derek:And until then, let me close with the parting words which I always give that I hope ring truer today at the end of this episode. Because you should realize at the end of this episode that saying peace must involve doing peace. Because it's in doing peace that not only are we moving with the fabric of the cosmos as God, a good God, has created it, but it's also how we love like our Savior did and it's how we restore things rather than perpetuate cyclical violence. We don't seek peace when we seek to take the life of another. So let me close with these words, a benediction of sorts.

Derek:That's all for now, so peace. And because I'm a pacifist, when I say it, I mean it.